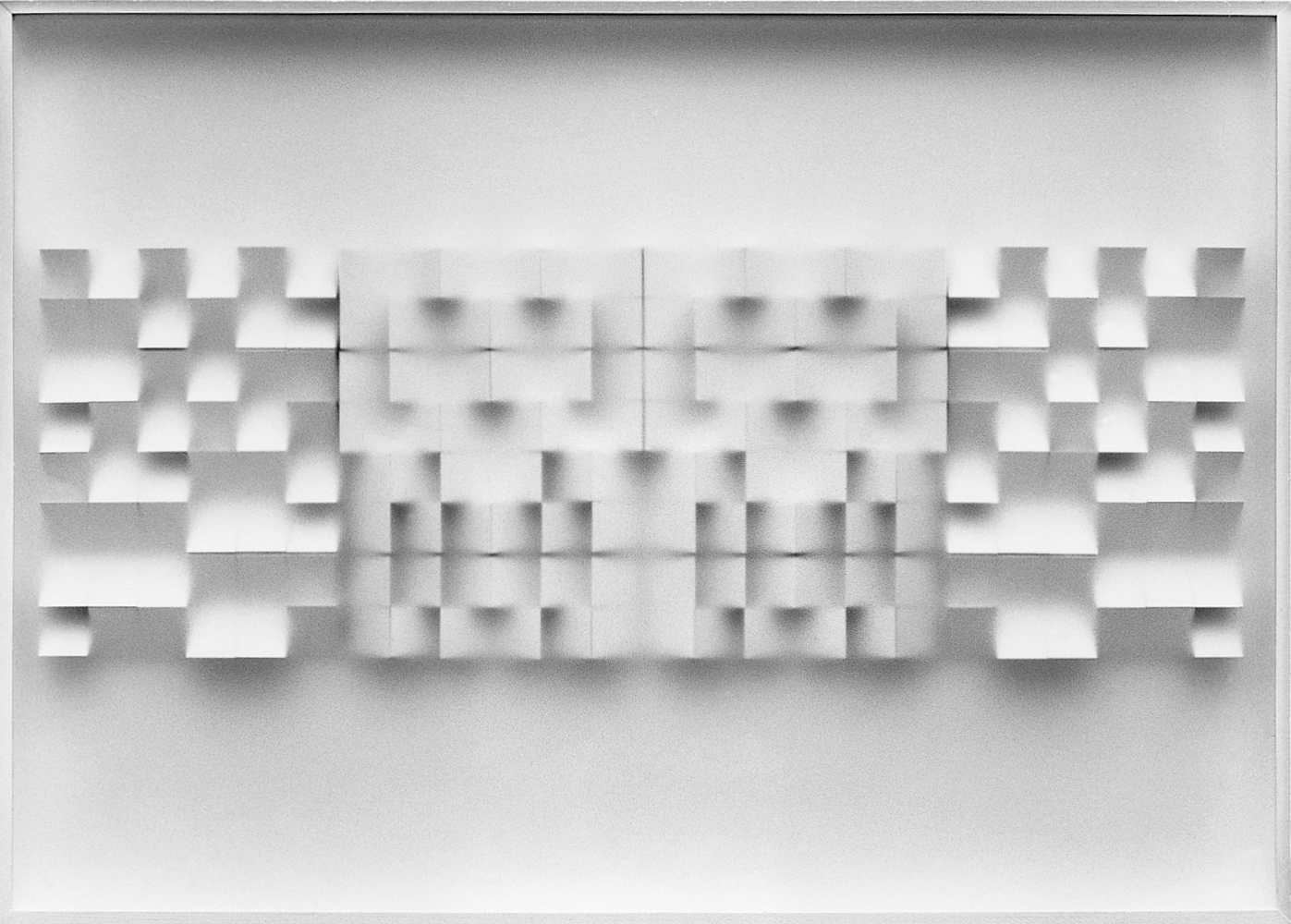

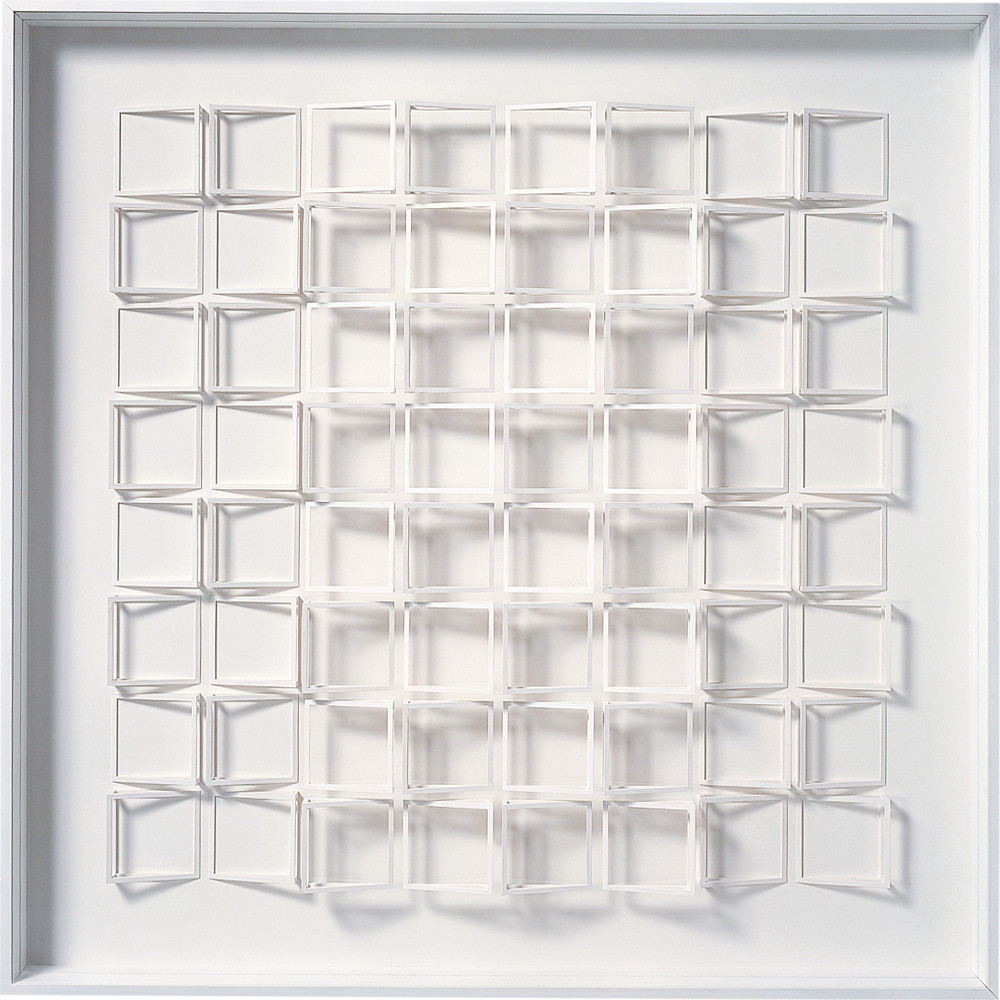

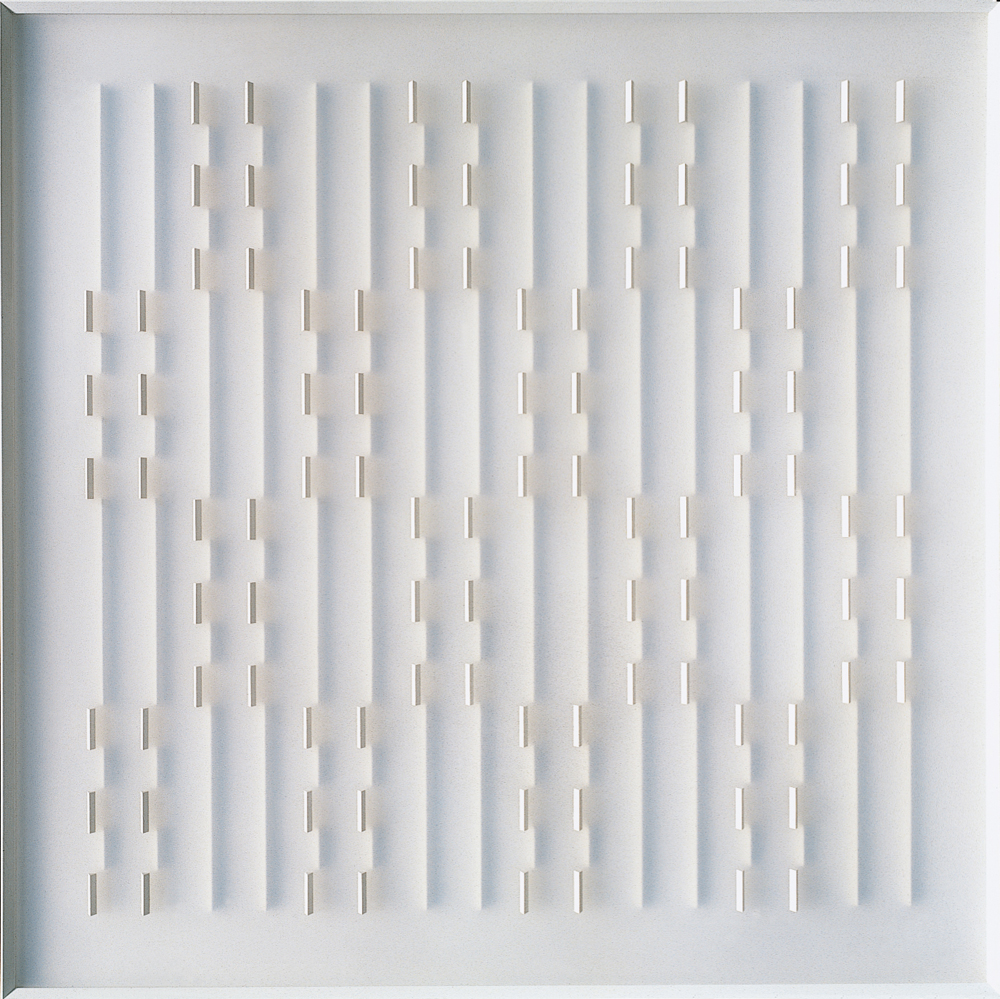

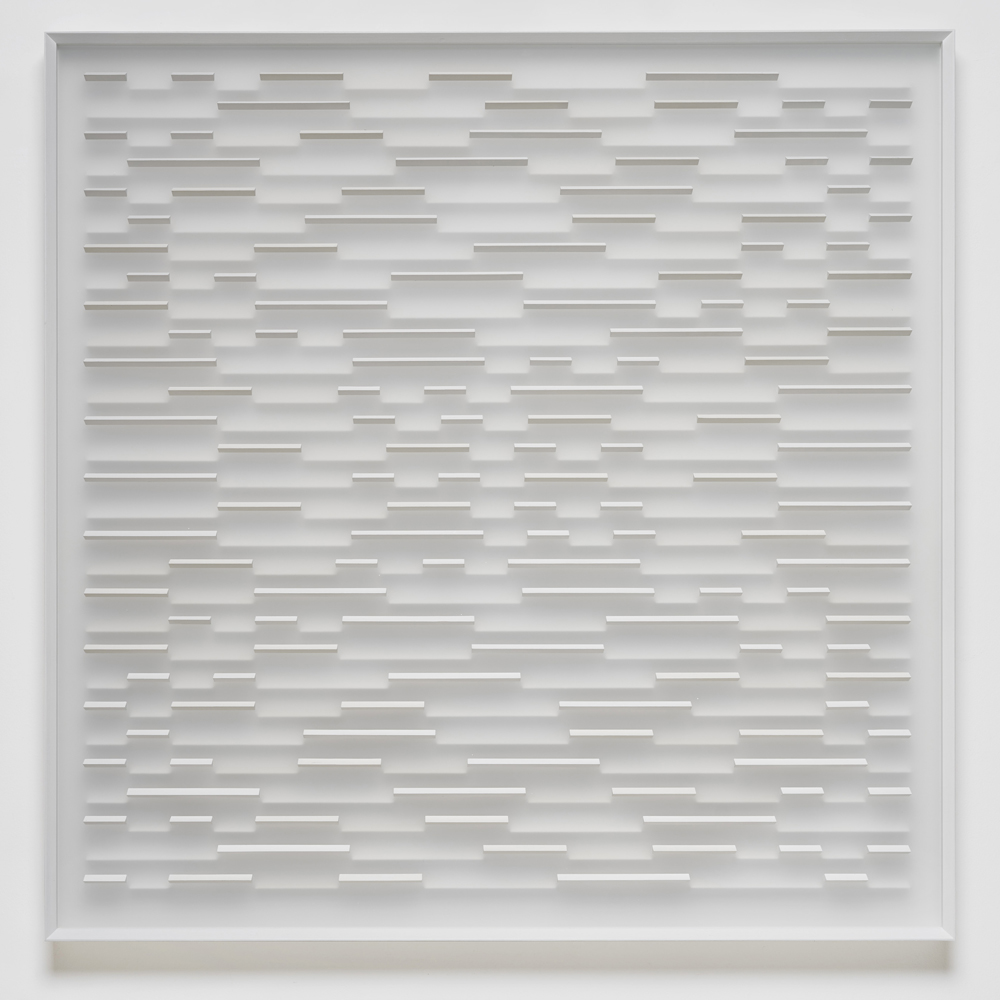

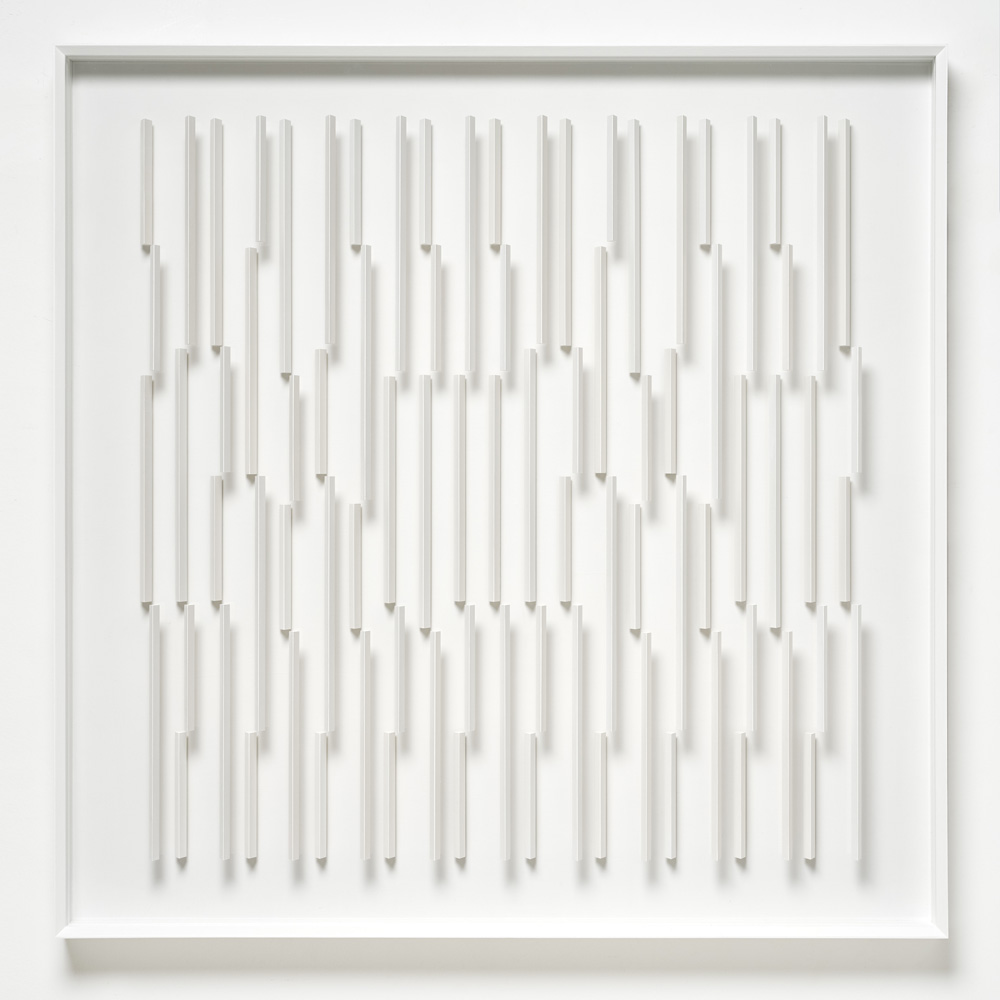

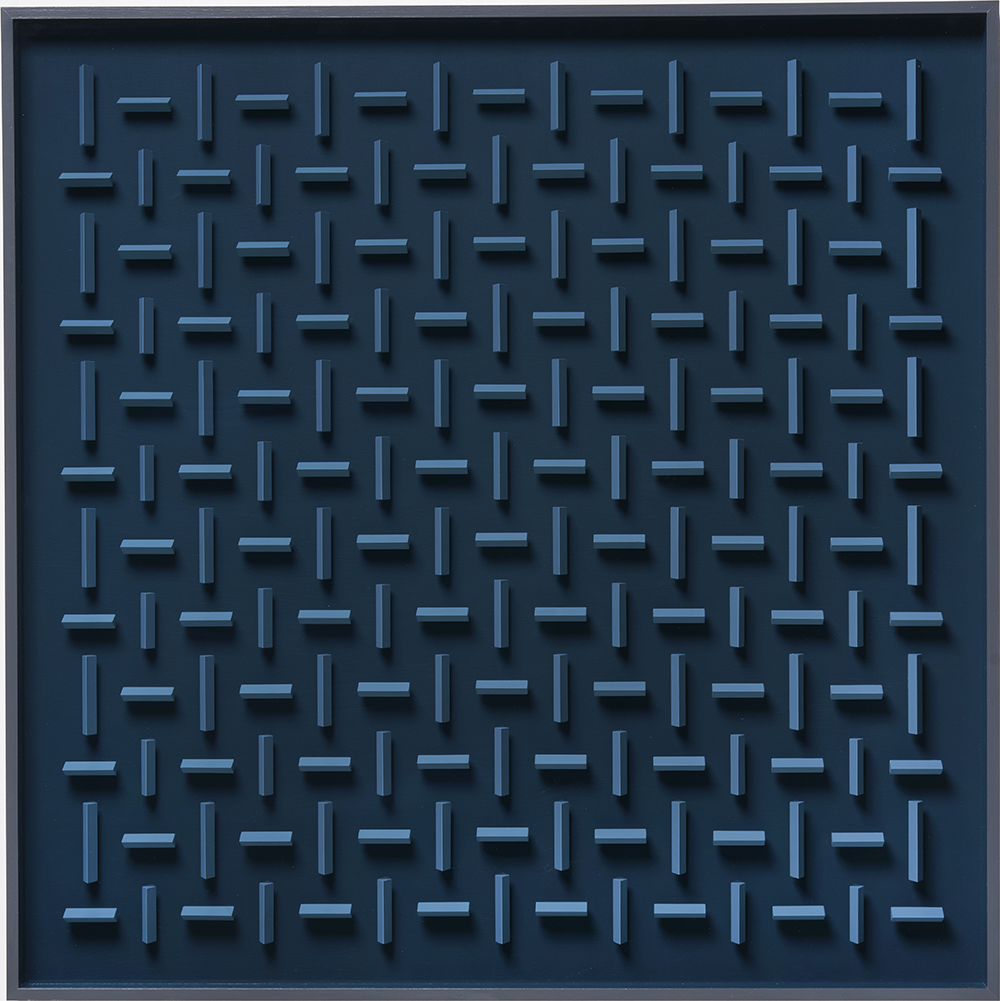

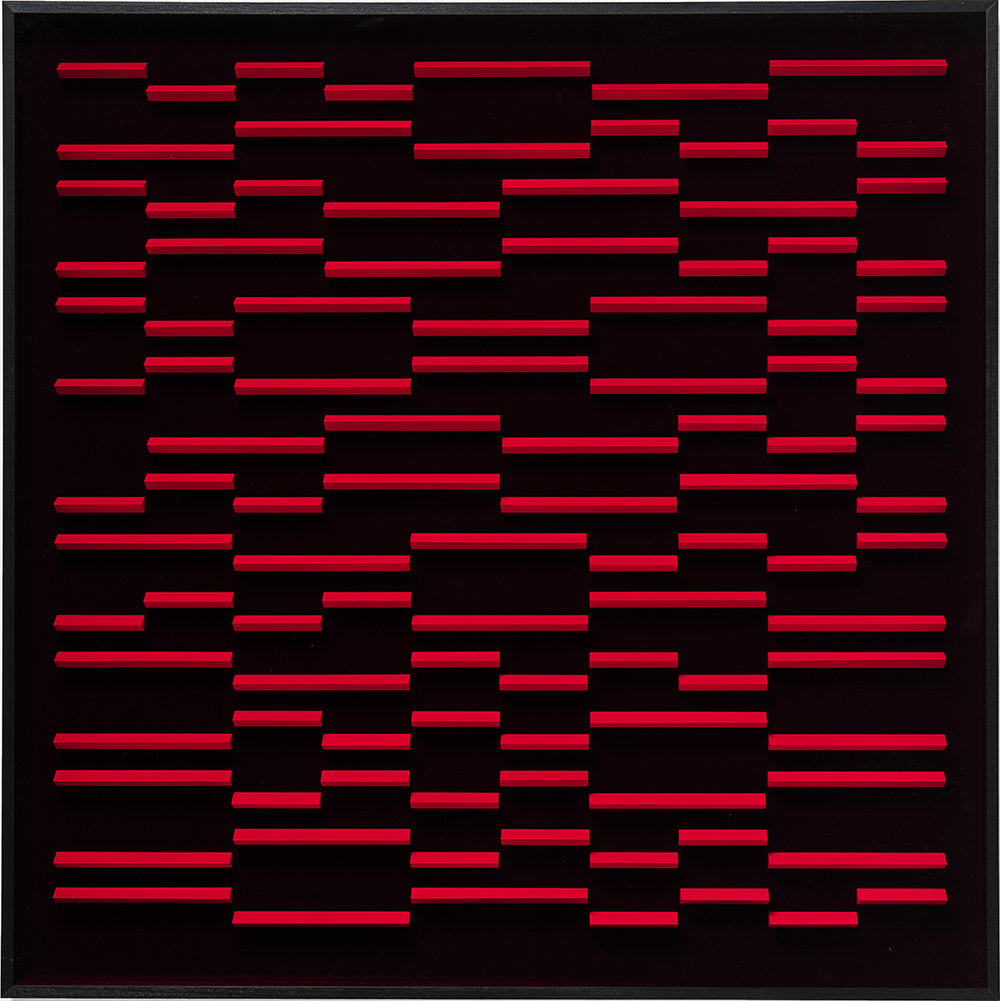

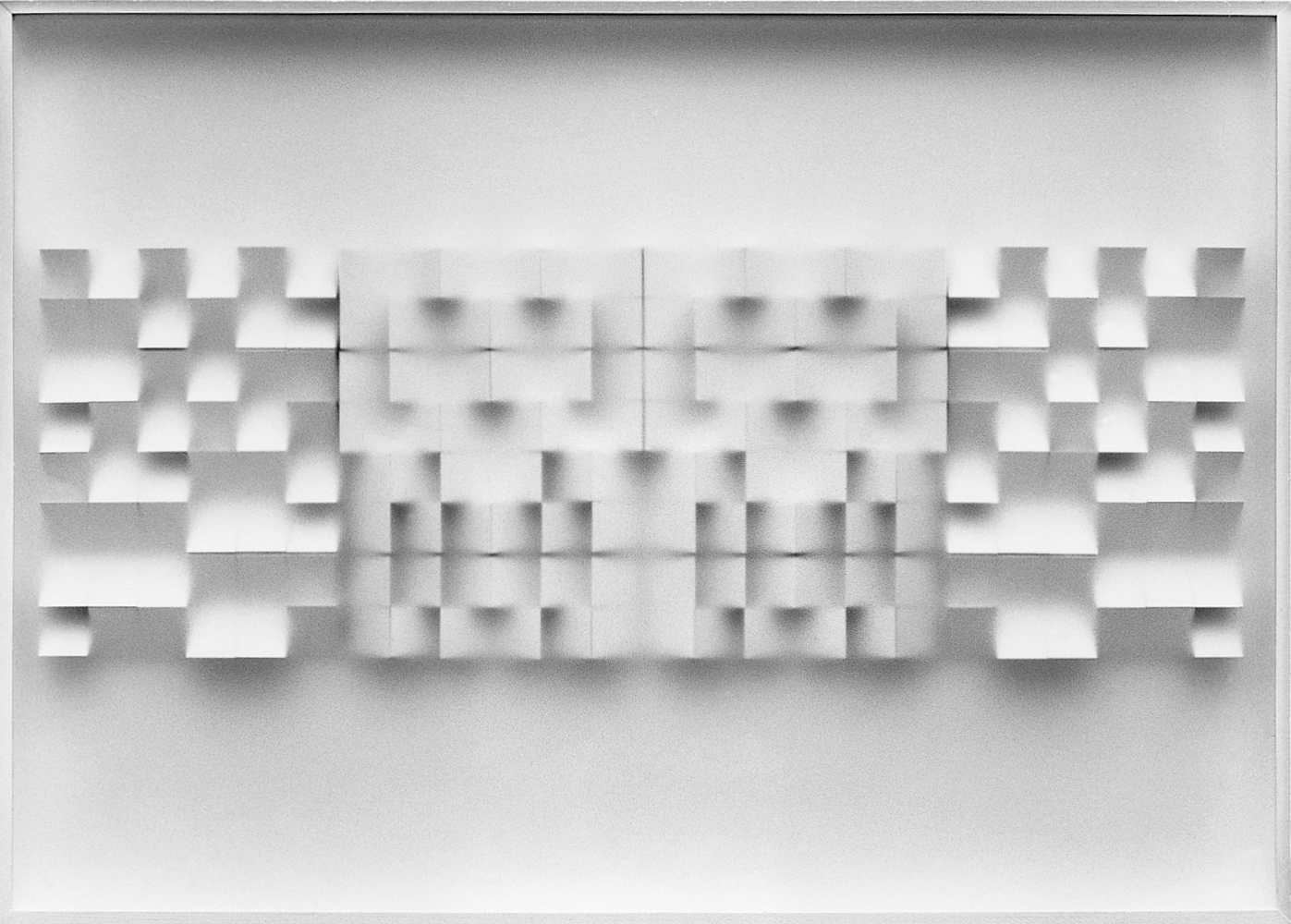

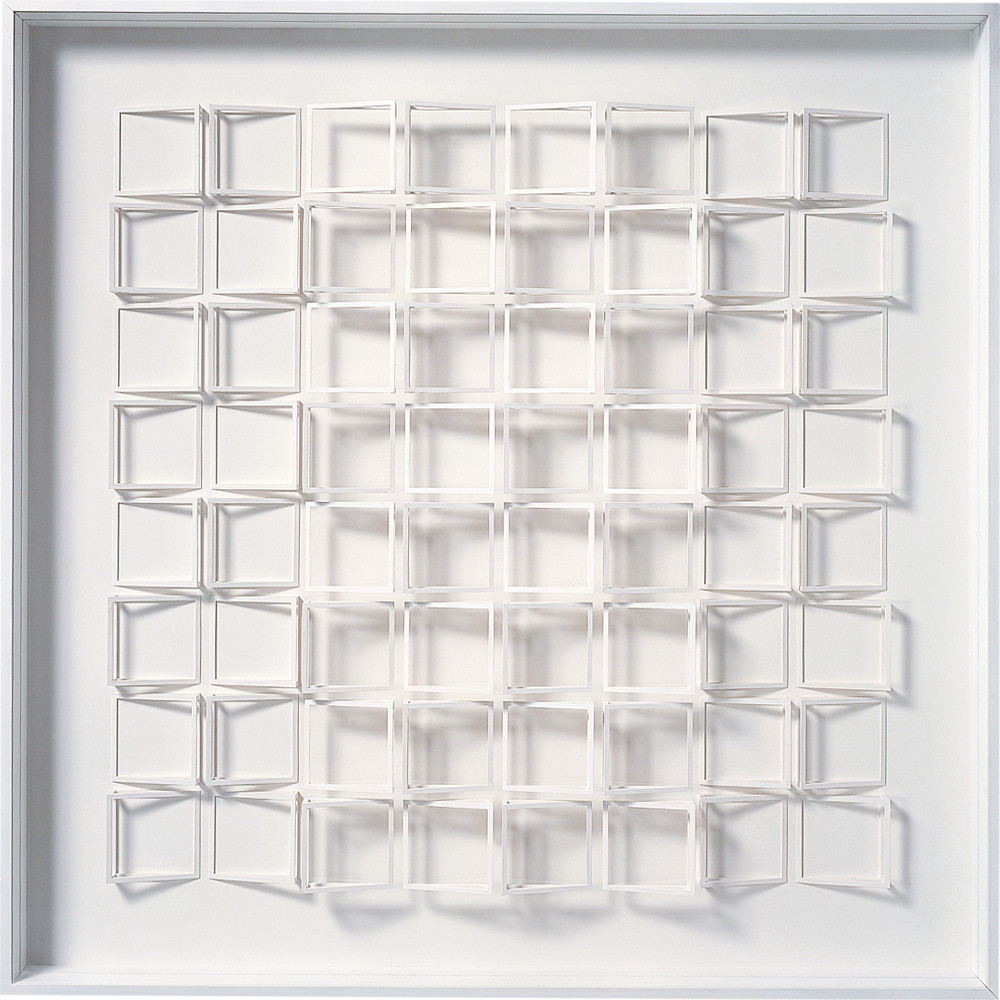

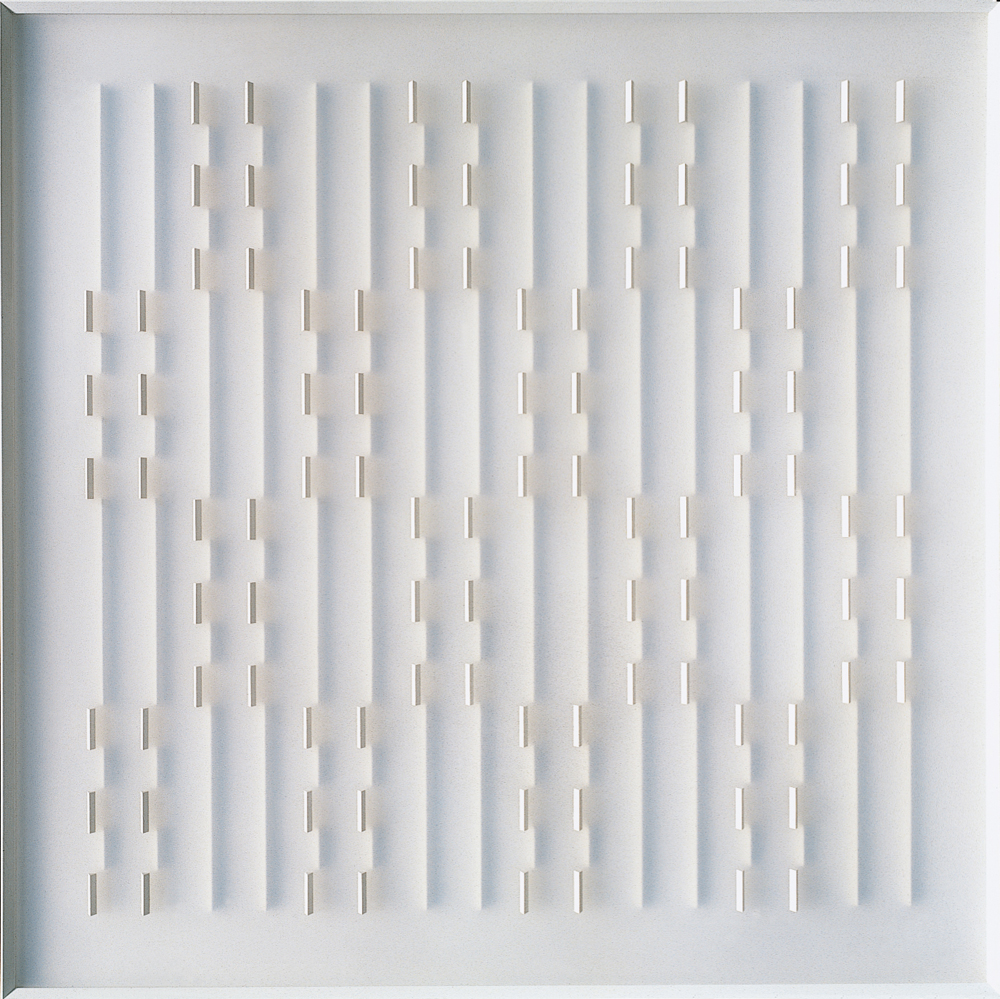

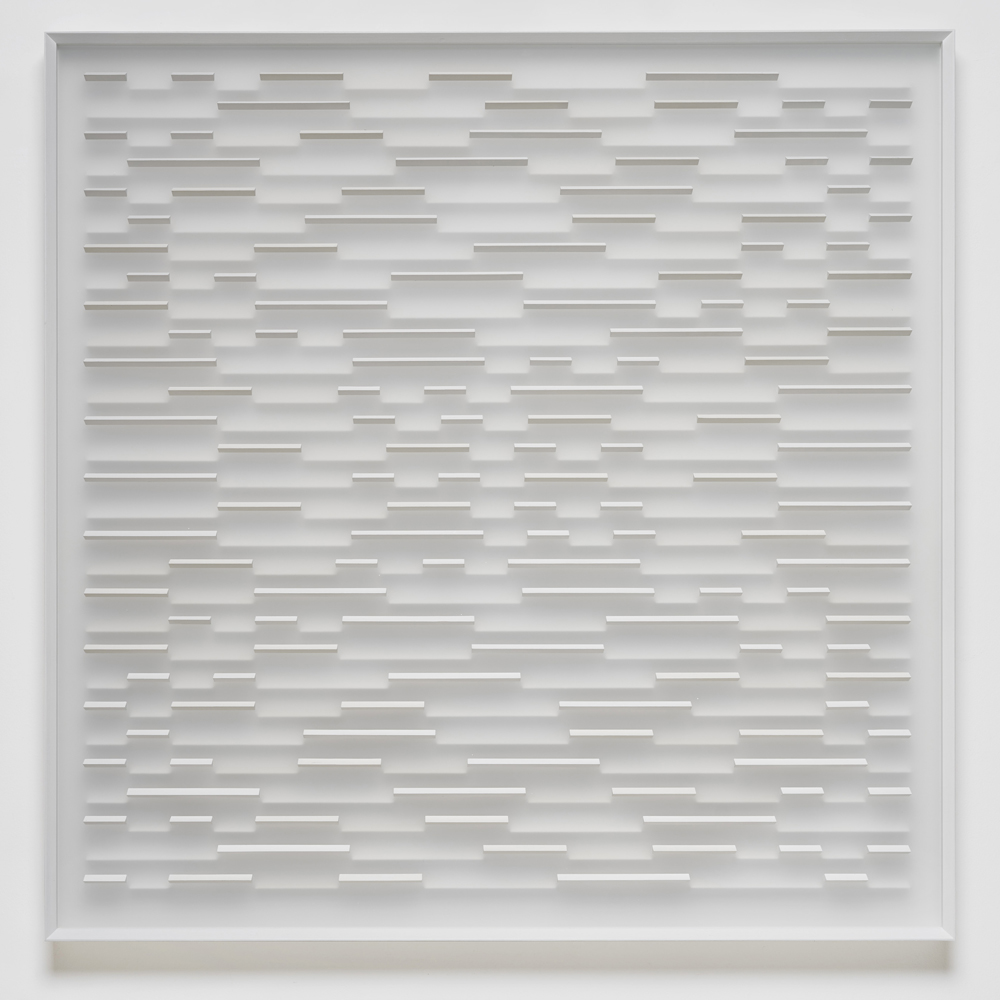

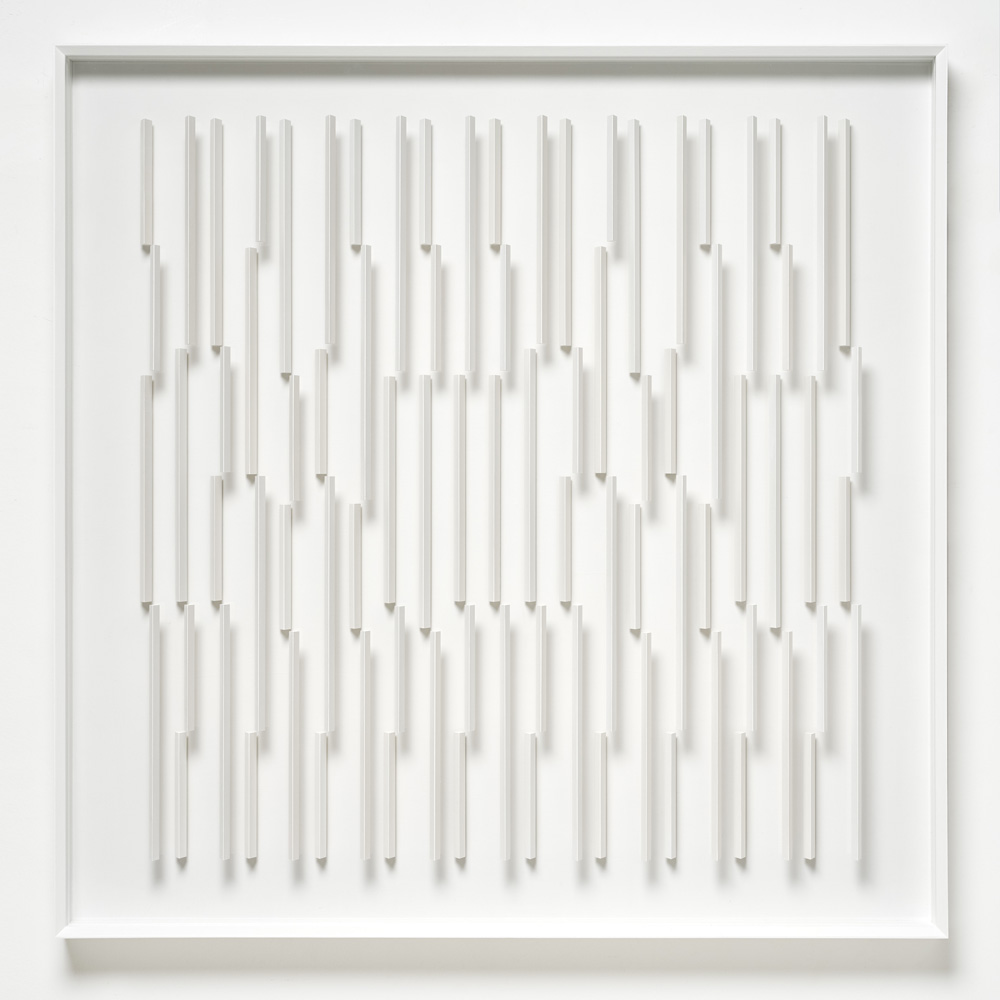

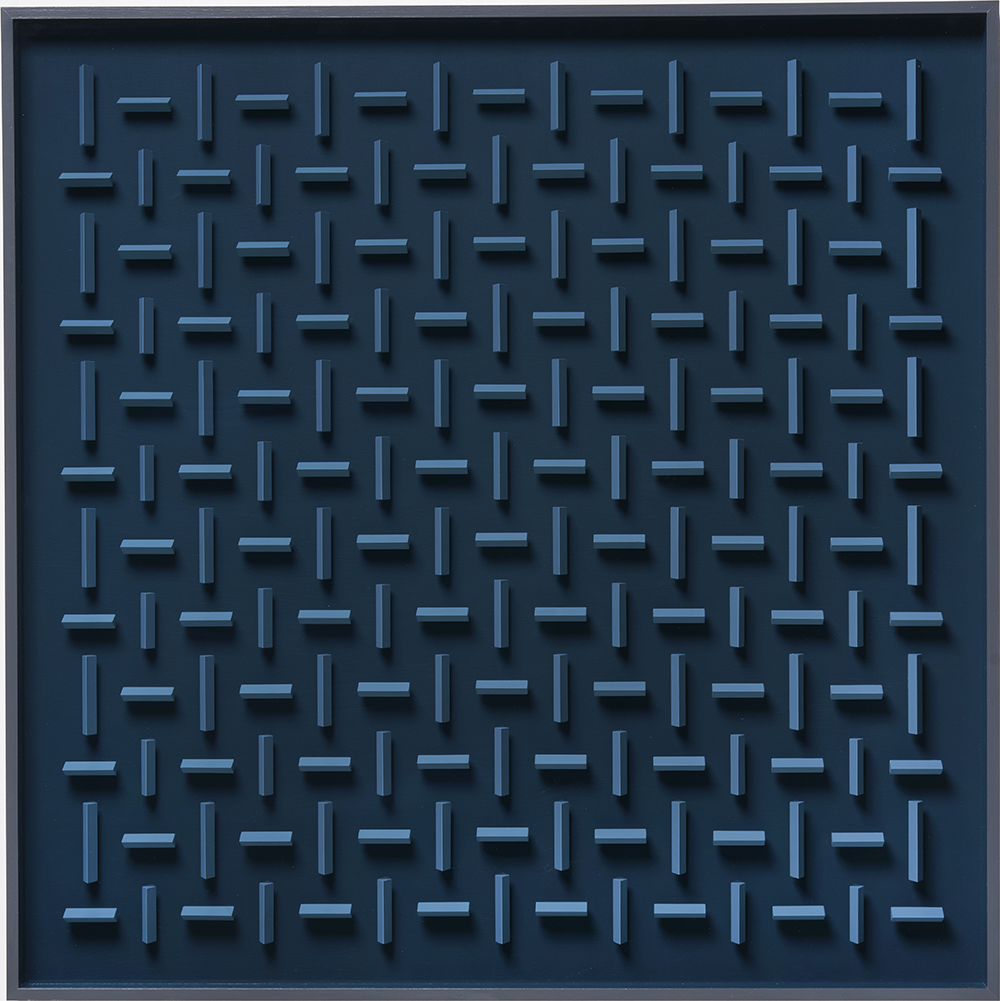

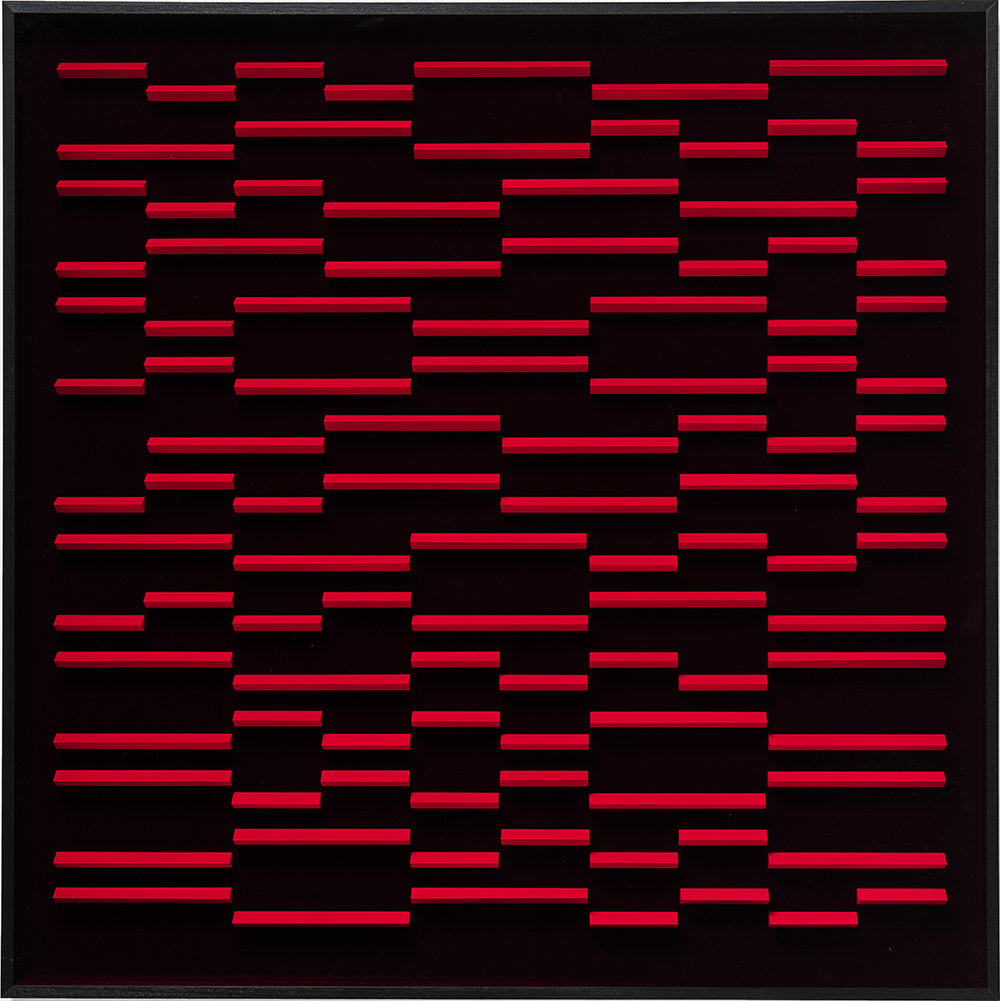

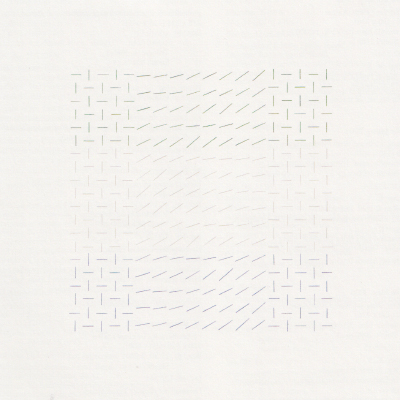

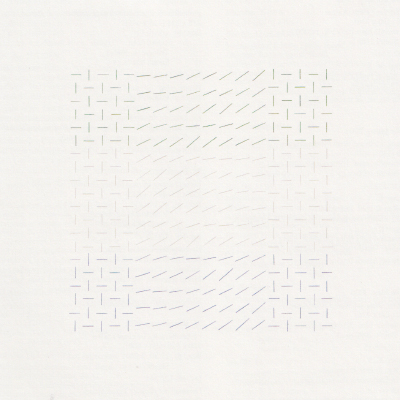

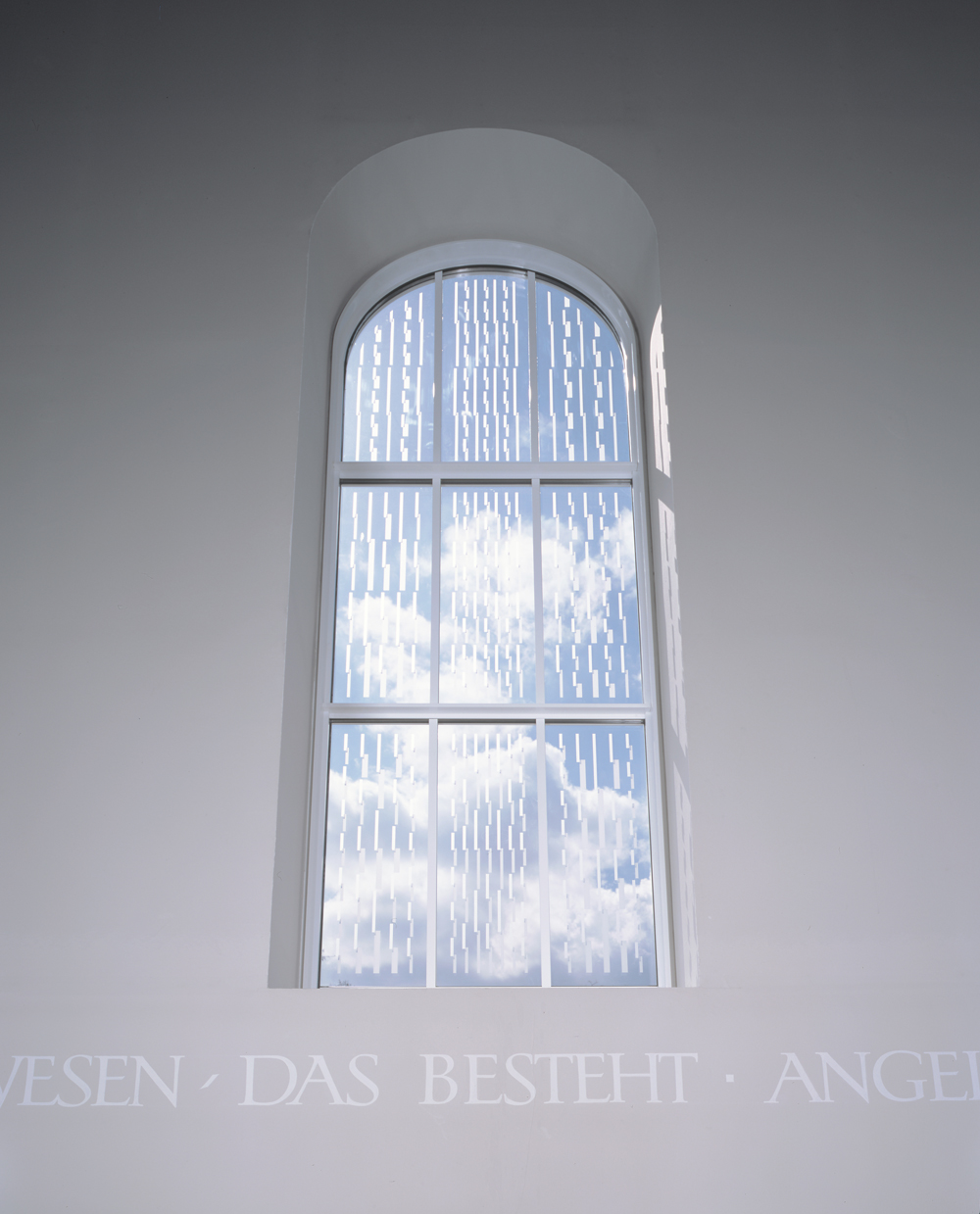

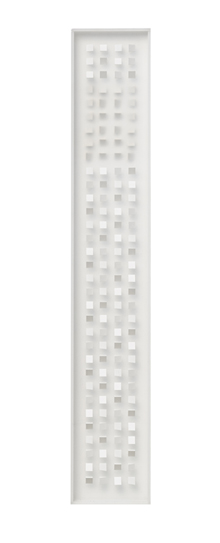

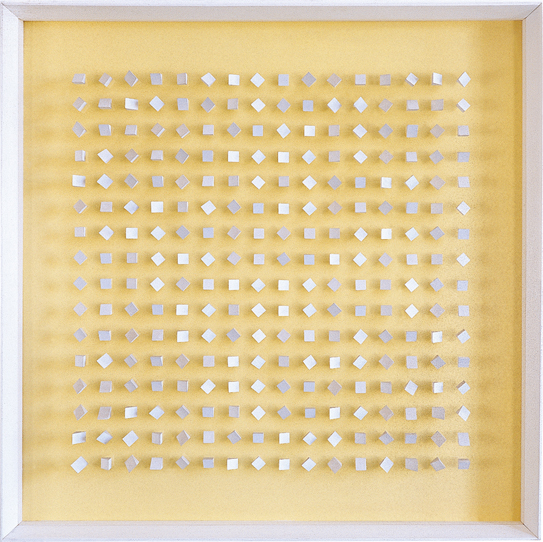

The serial reliefs developed since 1960 and serial objects created since 1967 relate mainly to the colour white, transparency, light and space, and include the viewer's interaction.

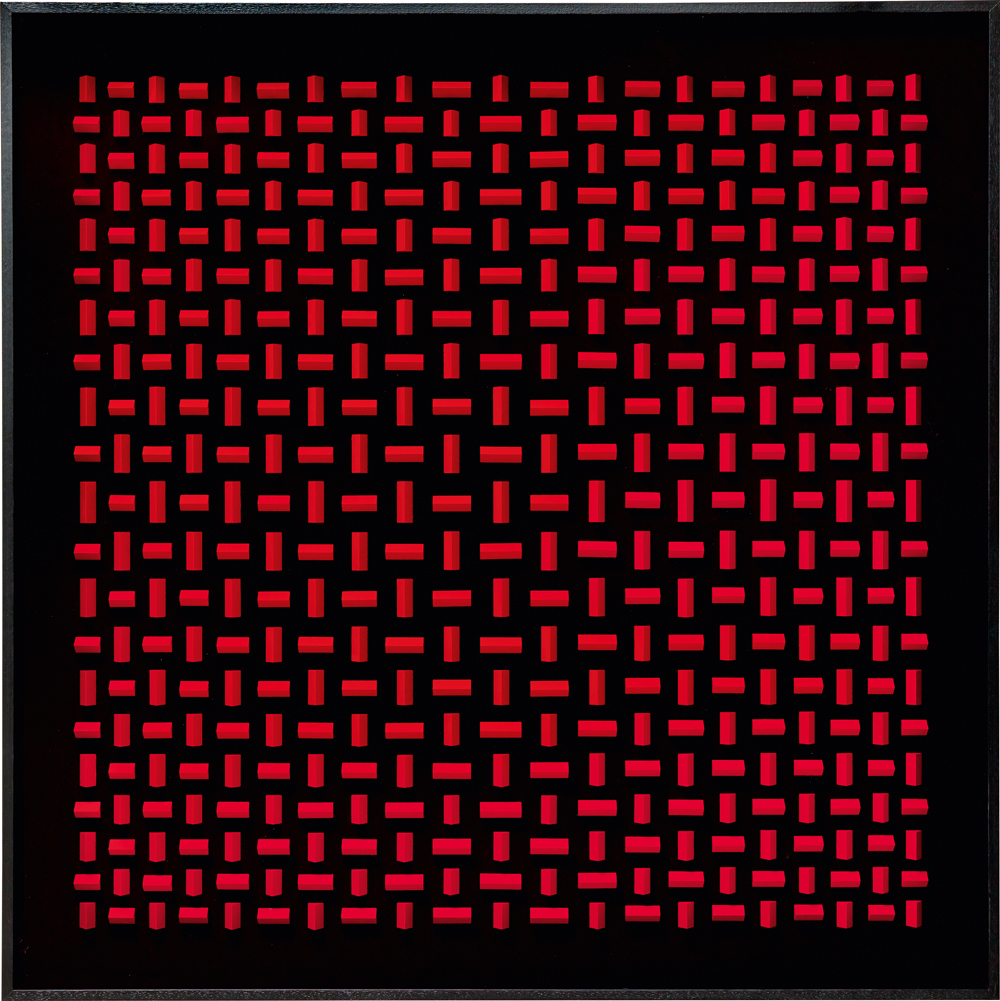

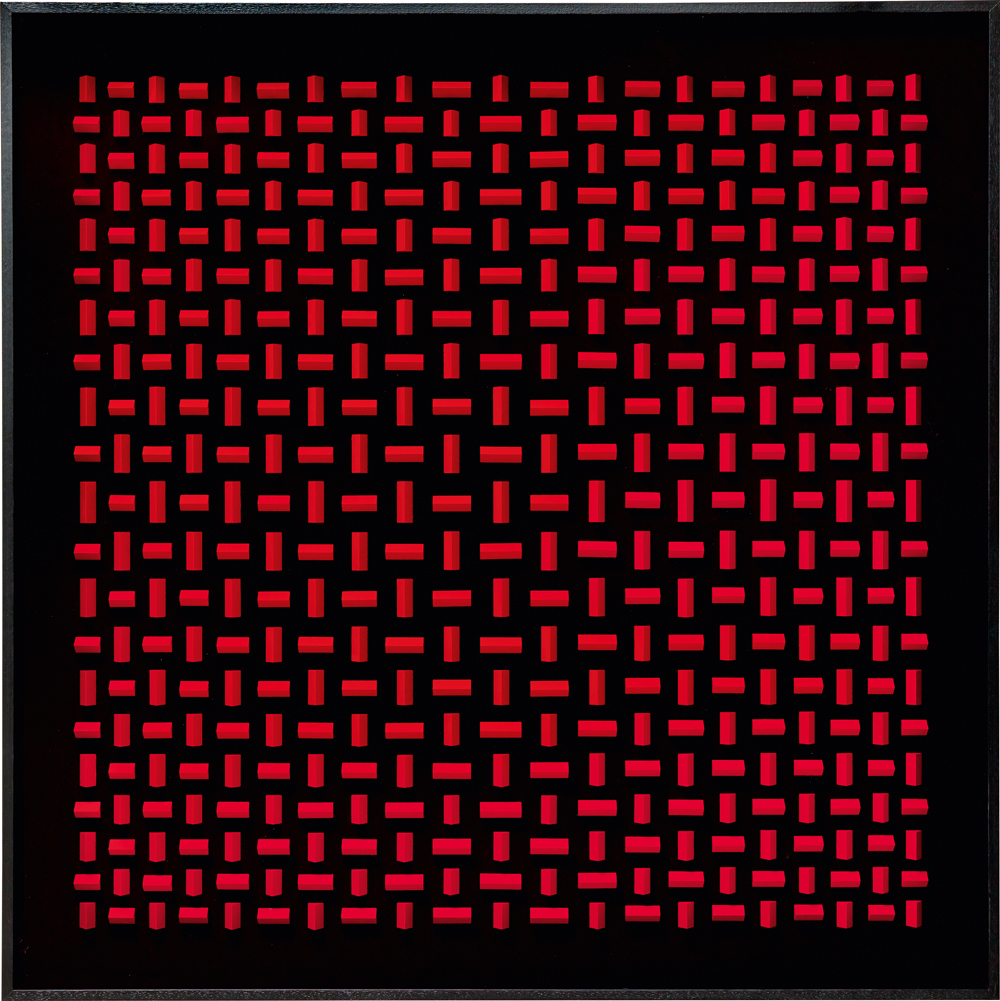

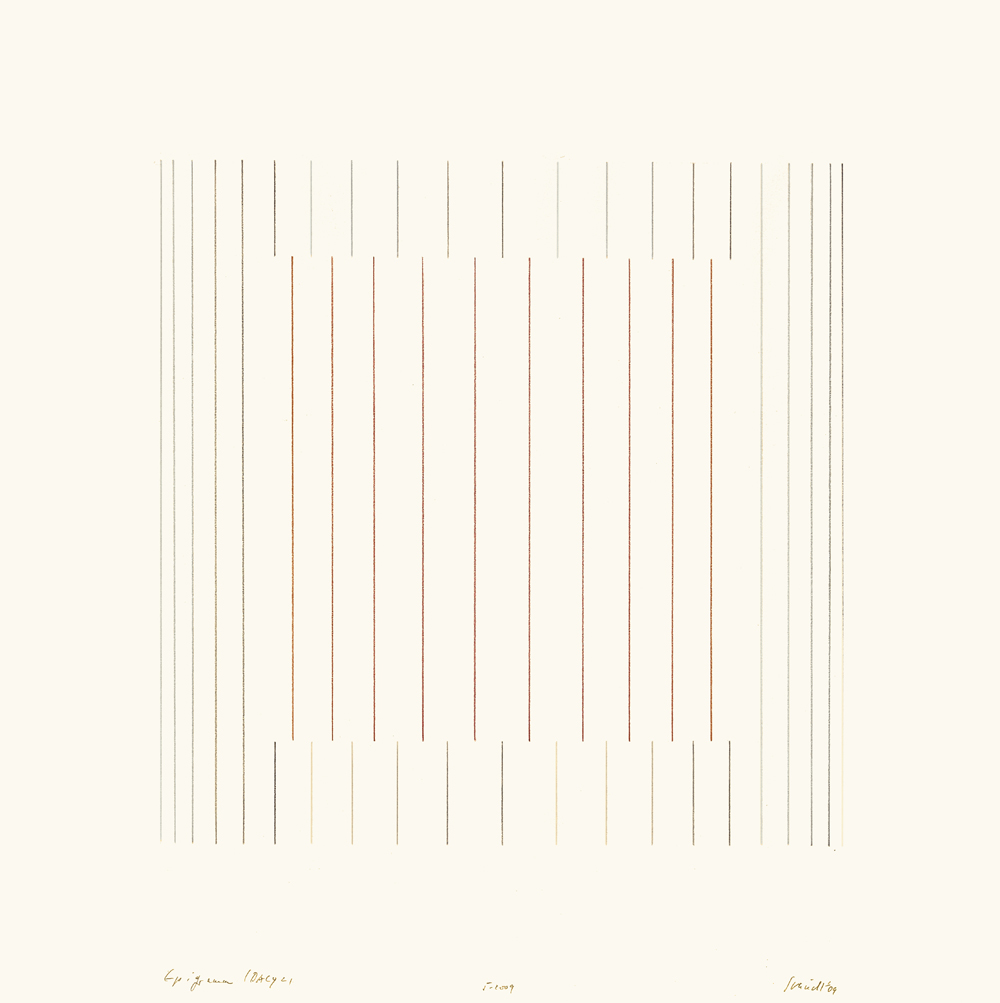

Transparency and semi-transparency embody the multi-layered nature of the objects. The transparent coloured objects developed since 1968 form the smaller group of works that continues to evolve at irregular intervals to this day.

.png)

.png)

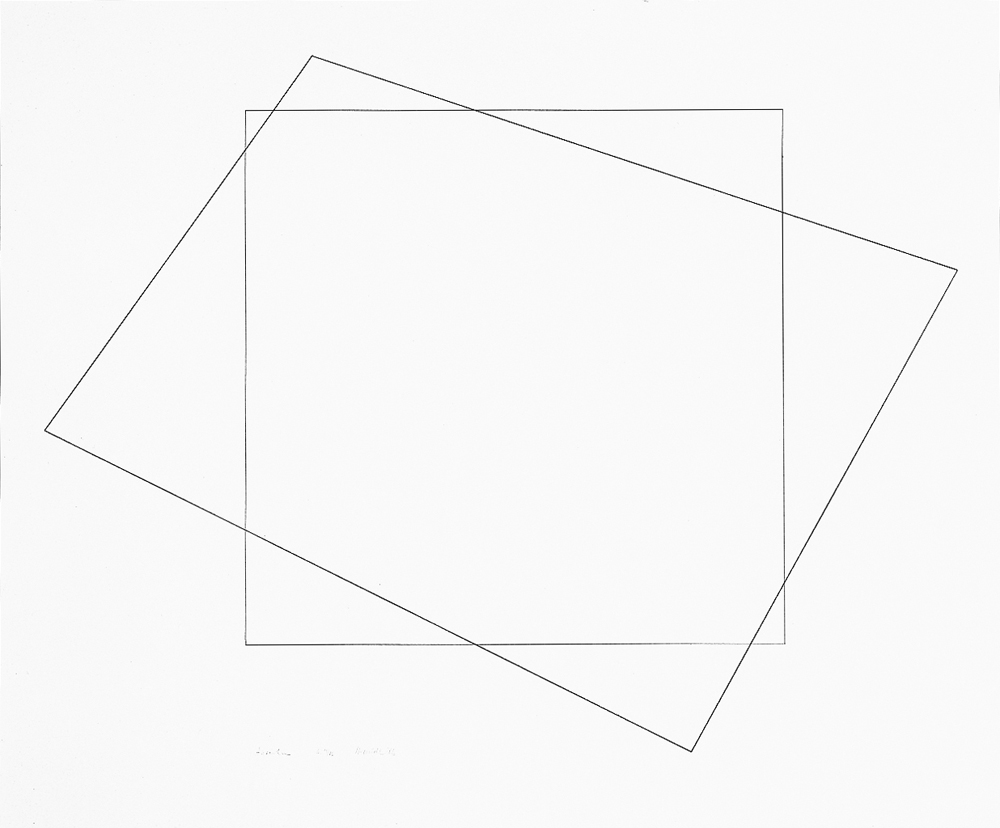

The double reliefs and sculptures continue the serial principle of the objects free-standing into the room, in that the white relief structures are stacked one behind the other in layers, or condensed into a central four-sided-closed structural core.

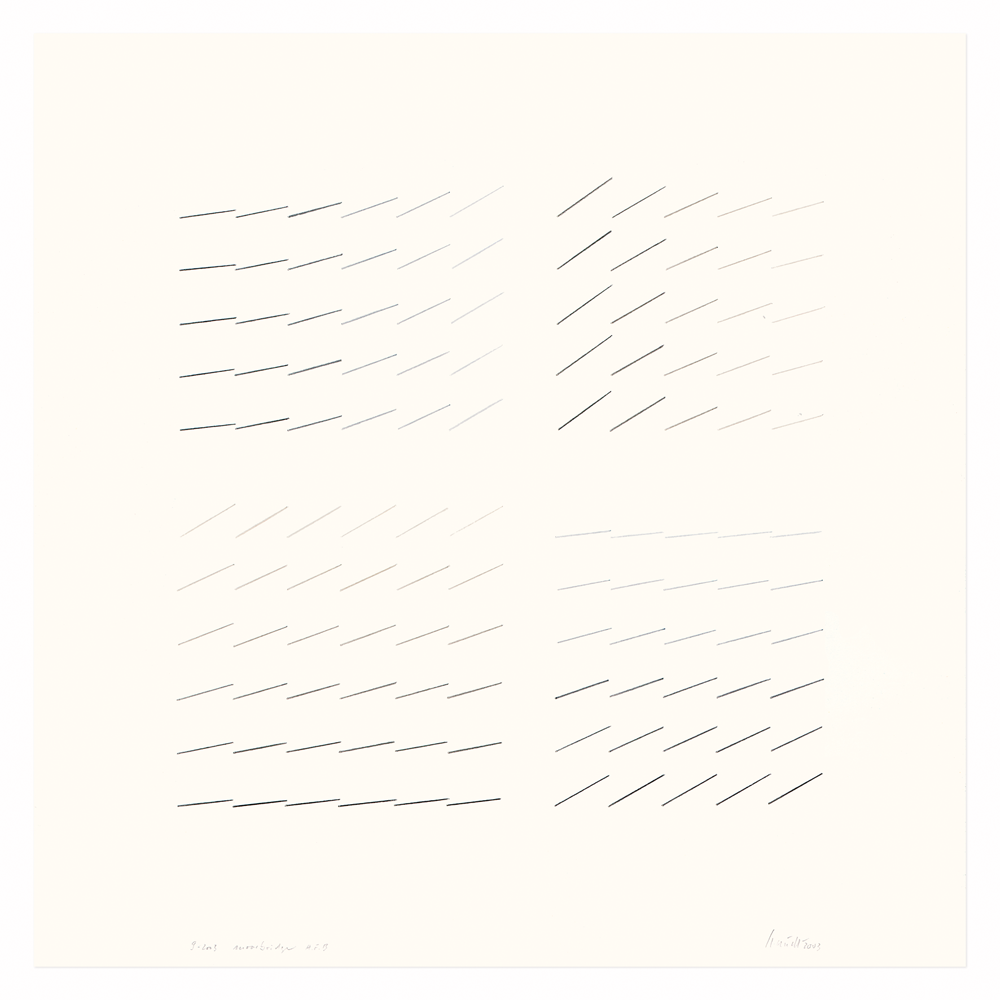

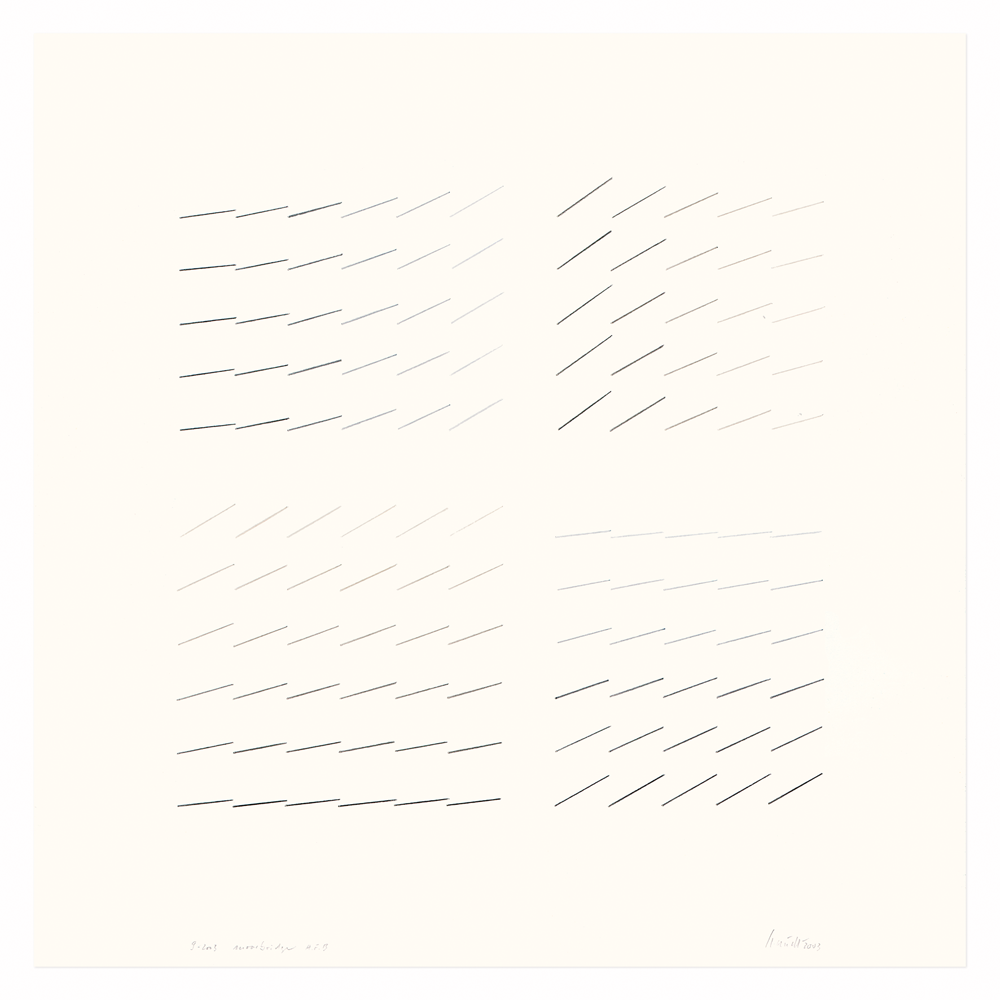

The drawings, which were created from 1970 onward and have been continuously developed to the present, form an autonomous group of works and have nothing to do with work drawings.

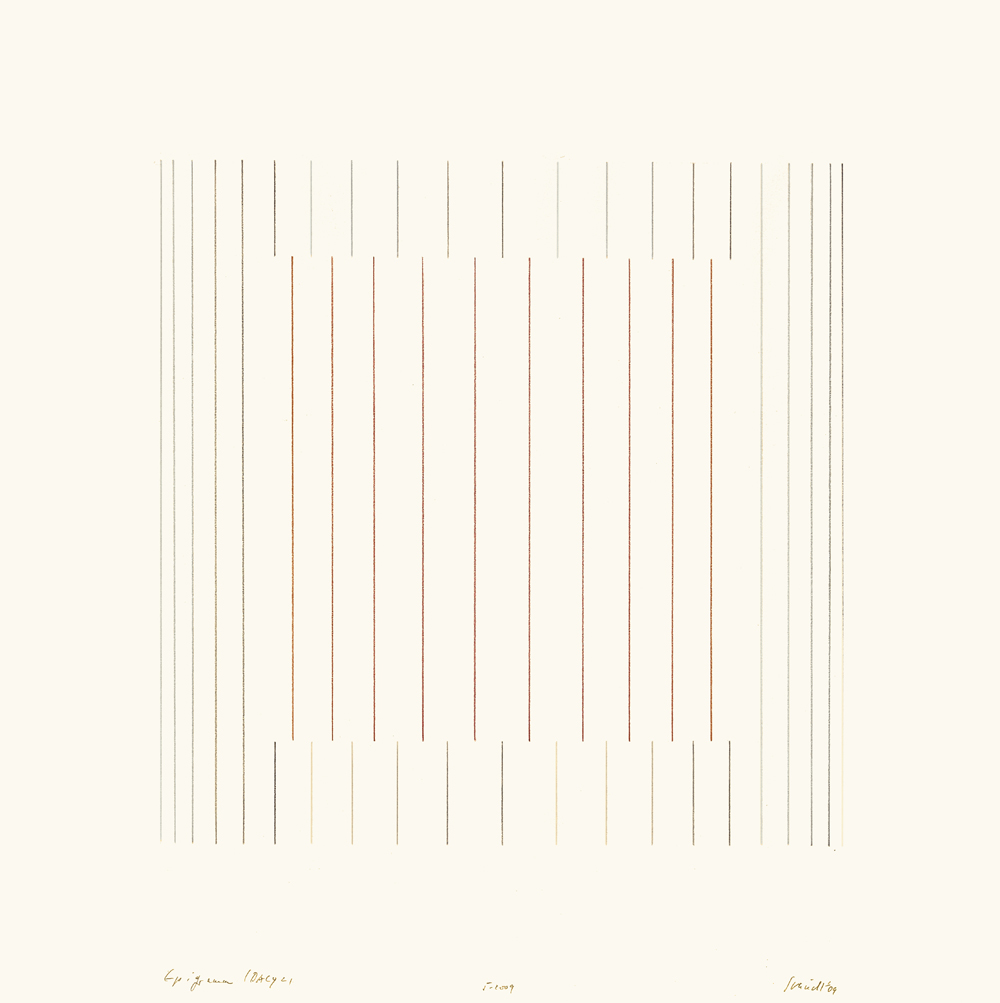

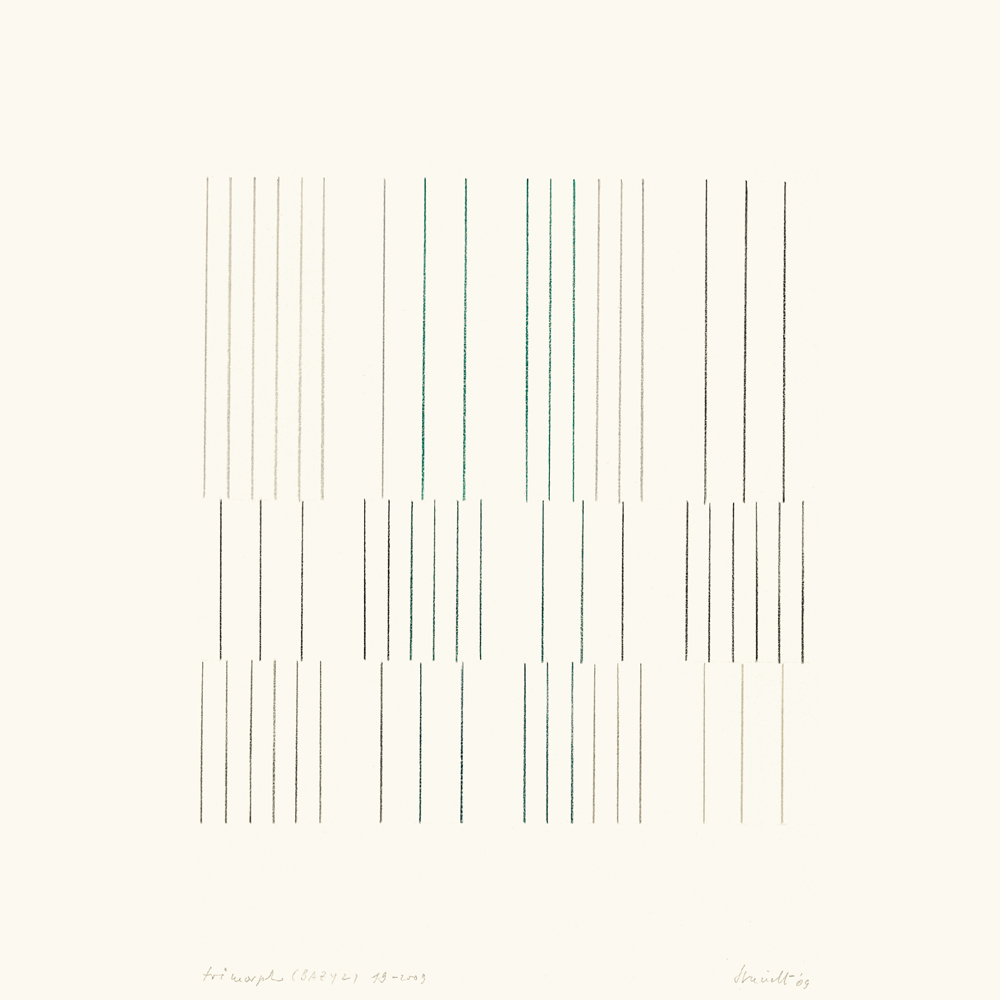

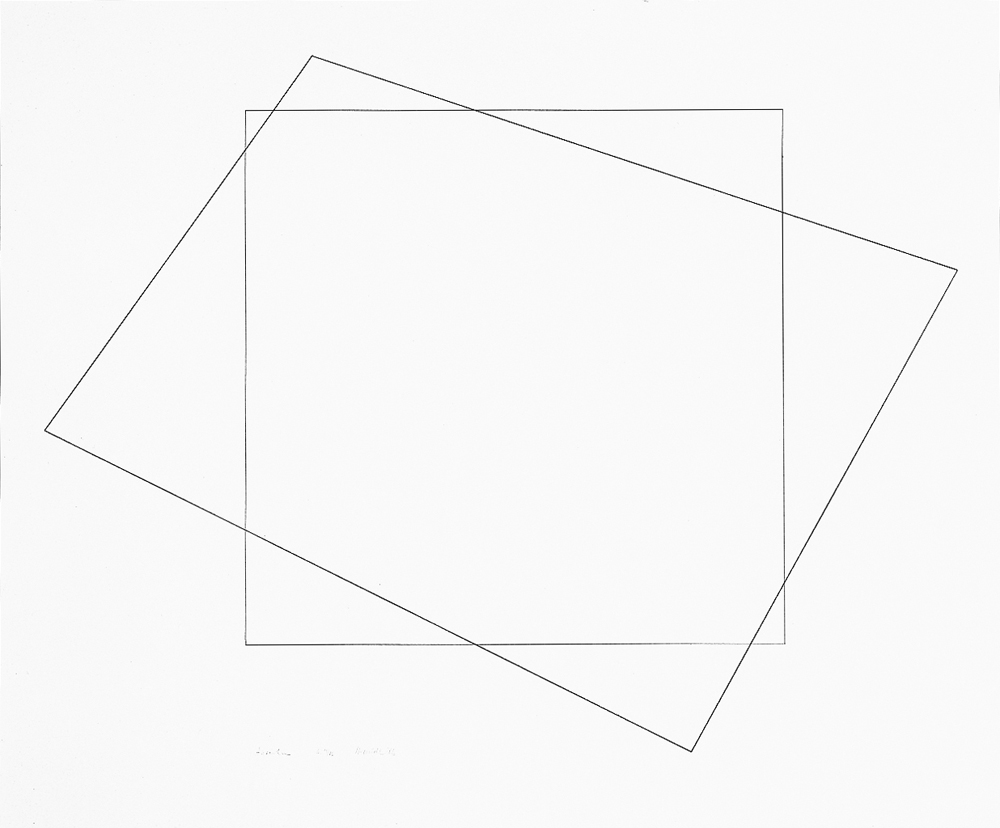

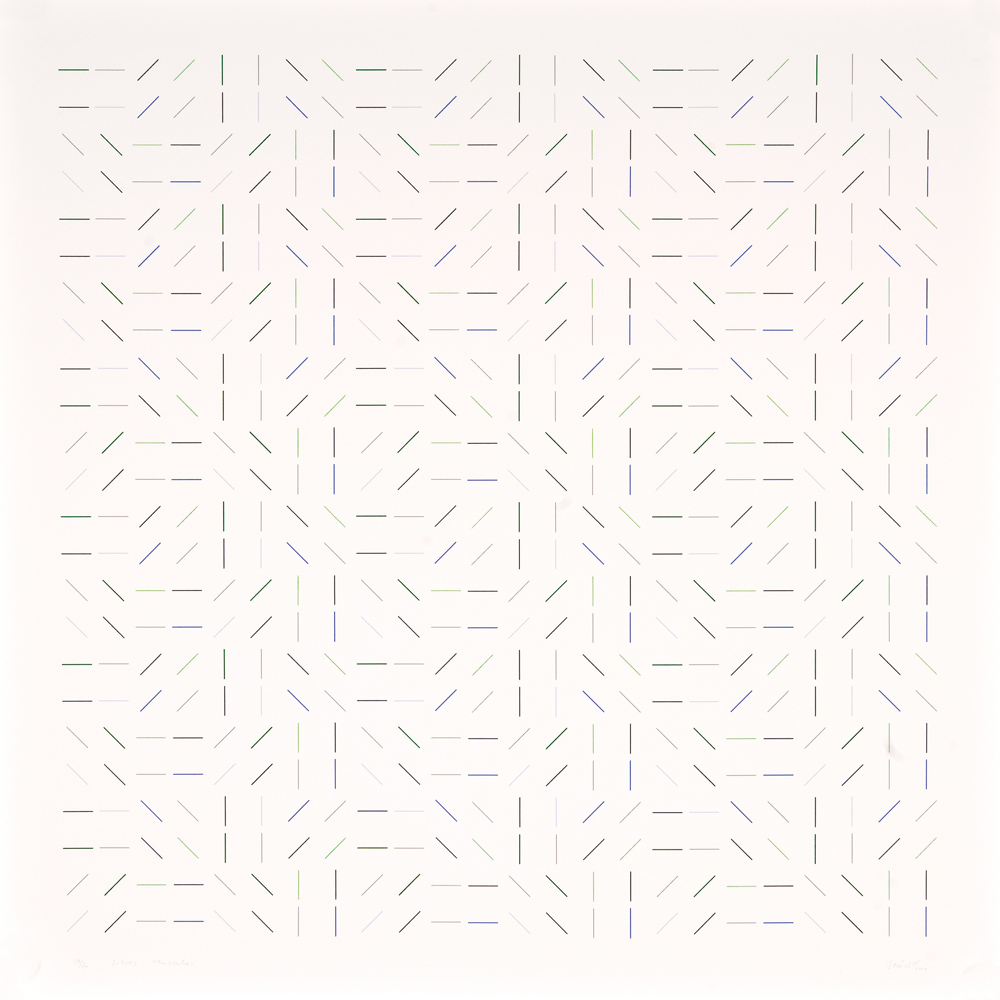

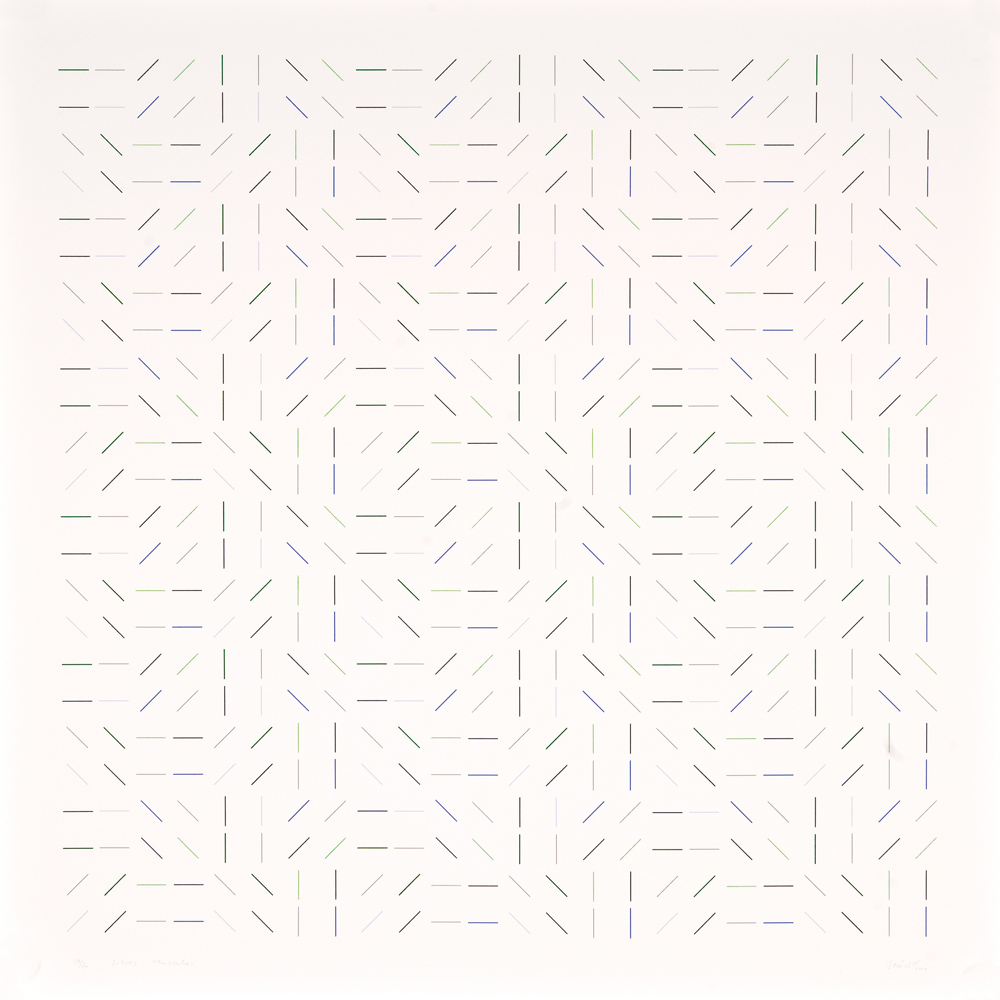

The principle of seriality also refers to the graphic arts, which Staudt has regularly developed since 1963 in the form of multicolour serigraphs, carton cuts, embossing and relief printing up to three-dimensional multi-layer Plexiglas objects, initially in larger and later in limited editions.

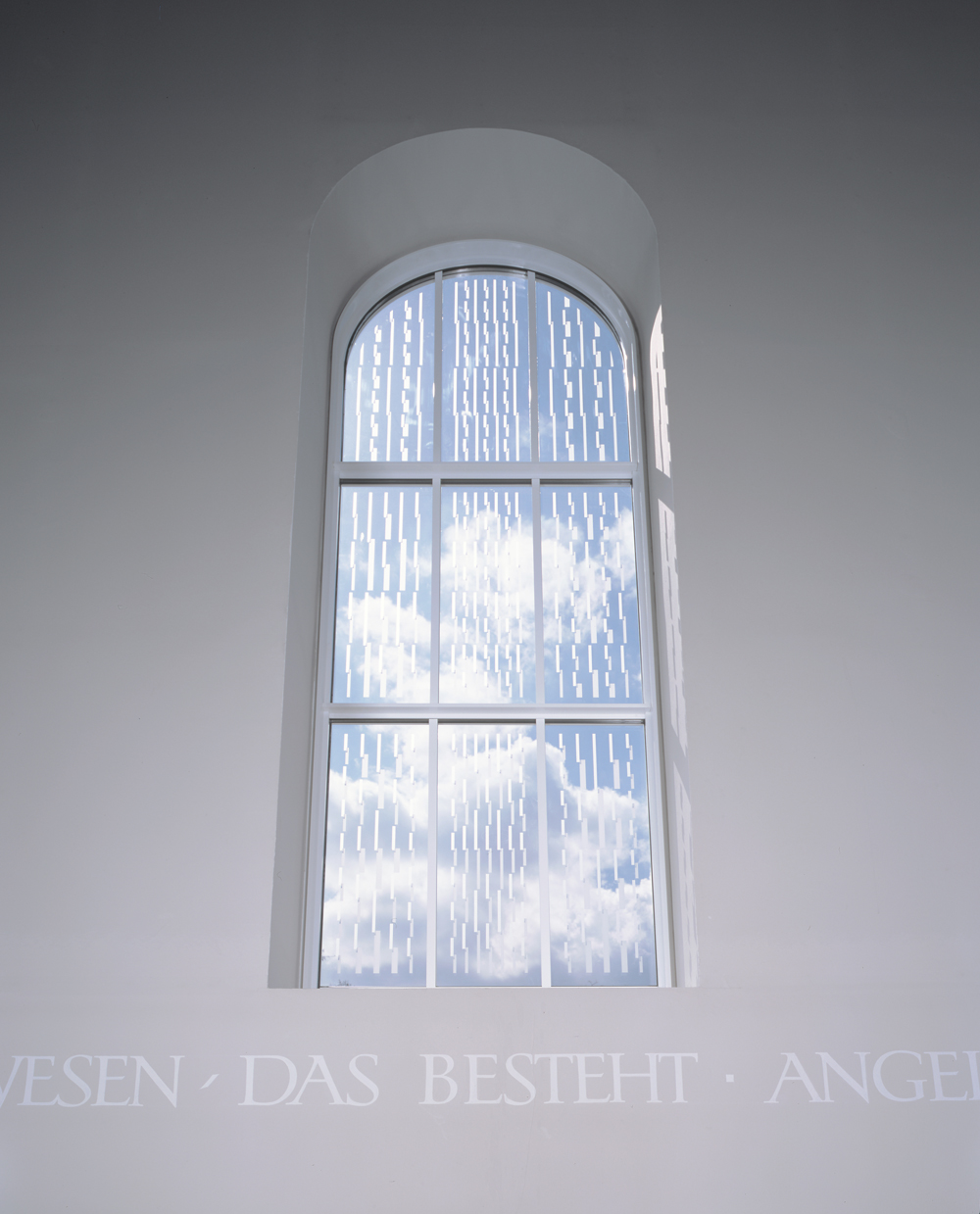

Both wall-related reliefs/objects and sculptures have been realized in architectural terms since 1963, among others in Augsburg, Berlin, Bremen, Felsberg, Ludwigshafen, Offenbach, Otterndorf, Stuttgart and Tostedt.

Born in the Westphalian town of Enger, Germany, in 1941. After studying Political Science, Sociology, Art History and Philosophy at Frankfurt University, he worked as a political correspondent for Deutschlandfunk and the Stuttgarter Zeitung in Prague from 1969 to 1973, for Deutschlandfunk in Bonn from 1974 to 1985 and for ARD Radio in Moscow from 1985 to 1991. From 1968 onwards he also worked as a freelance journalist for the arts section of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. From 1991 to 1999 he was editor-in-chief of Radio Hesse in Frankfurt and from September 1999 to December 2005 their correspondent in Washington, USA. Since the early 1970s he has written numerous essays on German and international politics and on art (in particular Eastern European art) for newspapers, magazines, catalogues and anthologies. He is also the publisher and author of several books.

Born in 1953. From 1987 until 1992 he was an academic museum assistant in training at the SMPK (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz) (National Gallery, Painting Gallery, Museum of Prints and Drawings). From 1992 until 2003 he was director of the Collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein. Since April 2003 he has been the curator of the Hilti Art Foundation in Schaan, Liechtenstein.

He has curated numerous exhibitions at home and abroad, including: 1989: Franz Erhard Walter – Drawings · Working Drawings 1957–1984, Museum of Prints and Drawings, Berlin, SMPK; 1994: Five Centuries of Italian art from the Collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein, Liechtensteinische Staatliche Kunstsammlung, Vaduz; 1998: “Gods Once Wandered...” – Antique Myths Mirrored in the Old Masters from the Collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein, Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz (1998–2003); 2005: From Paul Gauguin to Imi Knoebel – Works from the Hilti Art Foundation, Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz; 2006: Sean Scully – Die Architektur der Farbe / The Architecture of Colour, Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz; 2006: Gottfried Honegger – Les Pliages, Les Jardins du Palais Royal, Paris; 2010: Gotthard Graubner, Painting, Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz; 2015: Painting and Sculpture / From Classic Modernism to the Present Day, Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein/Hilti Art Foundation, Vaduz.

He also has a great many publications to his credit, including: ”The Function of Language in the Work of Franz Erhard Walter“, in: Franz Erhard Walter – The House Where I Live, Klagenfurt 1990; Five Centuries of Italian art from the Collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein, exhibition catalogue, Bern 1994; Masterpieces from the Collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein – Sculptures, Handicraft, Weapons, Bern 1996; “Gods Once Wandered...” – Antique Myths Mirrored in the Old Masters from the Collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein, exhibition catalogue, Bern 1998; ”Fruit and Sumptuous Still Lifes“, in: The Flemish Still Life 1550–1680, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna / Villa Hügel, Essen, Vienna 2002; ”Rocky and Mountainous Landscapes“, in: The Flemish Landscape, exhibition catalogue, Villa Hügel, Essen / Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna / Königliches Museum, Antwerpen, Essen 2003; ”Landscape – Real Experience and Artistic Form“, in: Hamish Fulton, Jürgen Partenheimer: Mindscape, Munich 2003; From Paul Gauguin to Imi Knoebel – Works from the Hilti Art Foundation, exhibition catalogue, Bern 2005; Sean Scully – Die Architektur der Farbe / The Architecture of Colour, exhibition catalogue, Milan 2006; Gottfried Honegger – mes sculptures dans les jardins du Palais-Royal, Ausstellungskatalog, Paris 2007; ”Gotthard Graubner – Painting as a Process and Phenomenon“, in: Gotthard Graubner, Painting, exhibition catalogue, Düsseldorf 2010; Hilti Art Foundation / Painting and Sculpture / From Classic Modernism to the Present Day, exhibition catalogue, Ostfildern 2015.

There is something in Klaus Staudt’s oeuvre that is so self-evident and compellingly logical that it has so far been deemed hardly worthy of particular consideration and reflection. This something is, namely, the grid. If we do give this aspect our closer attention, we shall inevitably have to answer the question concerning the function of the grid in almost all of Staudt’s reliefs and sculptures. While the artist himself is aware of its importance, it is interesting to note that he has devoted little attention to it in his many theoretical writings and observations on art.1 All the more reason, therefore, to rectify the omission, especially as there have been so many different artistic approaches to this particular device in the 20th century that it will be well worth while to subject it to closer scrutiny.

| CONTINUE READING |

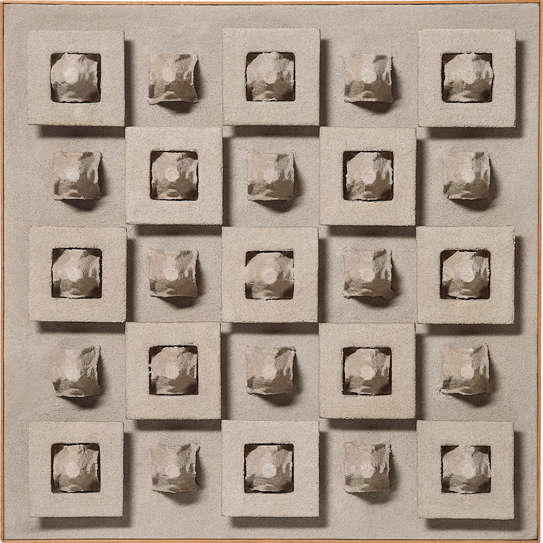

1960 was a decisive year in Klaus Staudt’s artistic development. Experimenting with everyday, commonplace materials, he discovered the technique of the relief and was then able to turn his back on painting, the medium in which he had been working hitherto. Still a student at that time, Staudt created a three-dimensional work from a simple egg box. It was the first of his serial reliefs based on an existing, industrially produced grid system. Staudt cut the egg box into its individual elements and mounted the cut-out cups onto a cardboard support of the same colour (Untitled, 1960, fig. 1). Every other cup was additionally framed with a square cut out of plywood. The resulting structure, which at first glance seemed very simple, developed its particular appeal – as do all the subsequent works of Klaus Staudt – through the interplay of light and shadow. The egg-box elements emphasized by the square frames, unlike their neighbours, cast huge shadows on the cardboard support. Staudt had made this effect possible by slightly raising the squares in relation to the egg-box elements. Thus it was that a typical feature of Staudt’s oeuvre had already made its appearance: the elements seem to hover over the support.

_1960.png)

Staudt’s modus operandi consisted in de-constructing a given grid structure – that of the egg box – in order to create a completely new, uniform grid from its individual elements. The measurements dictated by the industrial process were now replaced by Staudt’s own measurements. Indeed, within this series of reliefs there are also pieces that feature an irregular structure in which the grid pattern of the egg boxes is broken by square surfaces that virtually “eat” their way into the regular structure (Untitled, 1960, fig. 2). These works come much closer to those first works of Staudt’s that may be described as freely abstract. It is precisely for this reason that this egg-box series is so important, for it was during its production that Staudt not only made a decisive break with what had gone before but also developed his own original style.

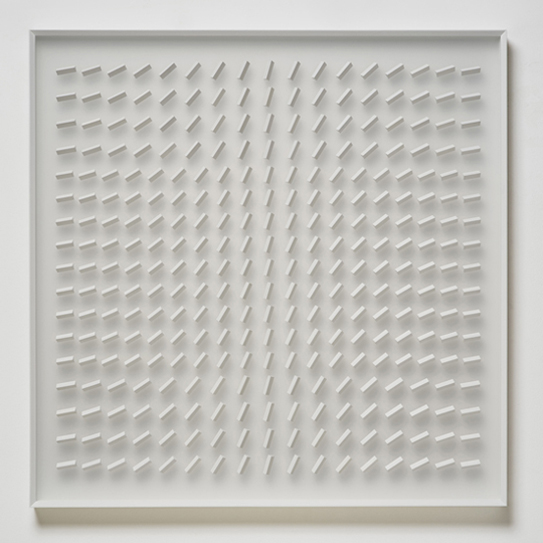

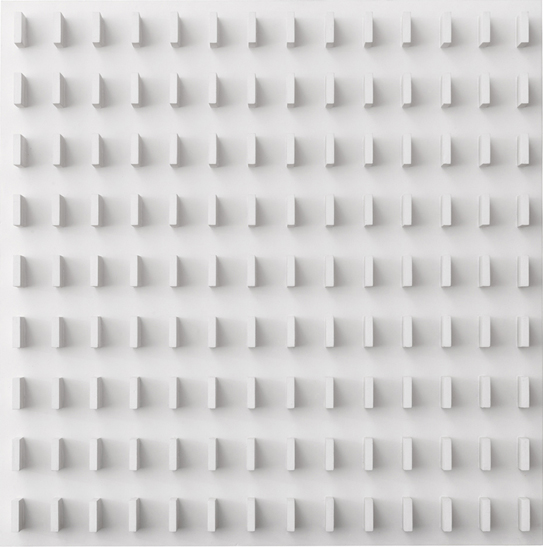

There then followed a number of reliefs that were extremely serial in structure, this aspect being further emphasized by the titles: Regular (Machine Relief 1) (fig. 3) and Emphatically Serial (fig. 4). With an excess of tiny parts, which was later to be quite atypical of his oeuvre, Staudt repeated the same geometrical solid – based on either the square, the oblong or the triangle – on a supporting panel. The perfect execution of these reliefs conveyed the impression that the works had been industrially mass produced. This rapport with industrial production was an important point of reference for many artists at that time, and in most cases the theme of the grid went hand in hand with it.

For the Munich student Klaus Staudt 1960 was also a year in which he made initial contacts that were to have a significant bearing on his future career. It was in Munich, together with Gerhard von Graevenitz and Jürgen Morschell, that he founded the “galerie nota”. The friends’ first artist to be exhibited at the gallery was the South American Concrete artist AlmirMavignier, and it was through this exhibition that they made contact with the Ulm College of Design and with Kurt Fried, who ran the legendary “studio f” in Ulm, a meeting place for Concrete/Constructivist artists. These contacts in turn gave rise to further contacts, such that by 1963 Staudt was already among the artists participating in the exhibition “NoveTendencije” in Zagreb, which during the years that followed took place at other venues under the same title and was intended as a rallying point for the young European avant-garde. What the majority of these artists all had in common were the grid, the colour of white and the interplay of light and shadow. Moreover, they all shared a large overlap with the national art movements: Zero, GRAV, Gruppo N, Gruppo T and Nul. Why, then, was the grid so central to the work of these artists?

There were two decisive aspects: on the one hand there was the fascination for the paradoxical properties of the grid that were to be found everywhere in society and stood symbolically for modernity and, on the other, there was the multitude of kinetic and optical effects achievable by means of the grid. In post-war art, from 1960, there was a definite new beginning that manifested itself in the aforementioned “New Tendencies” through a radical break with tradition – back to zero, back to square one. While the colour of white was seen as the epitome of this purifying return to a new beginning, it was – on a more practical level – ideal for experiments with light and shade in conjunction with the grid. The grid served GüntherUecker in his early nail reliefs as an anonymous structure, permitting him to avoid an emotional, casual style, whereas Piero Manzoni, for example, created his “Achromes”2 by mounting banal, everyday objects – mostly left in their natural white state – in serial form on a support. The grid in its most extreme, dense form could also produce such optical effects as the moiré pattern, which made it ideal within the context of Op Art.3

The grid is the essence and epitome of modern, serialized mass production, which since the inception of industrialization has become more and more standard. But this process of standardization goes far beyond the manufacture of products. Methods of recording data on the individual – used by governments, medical institutions, law courts and scientists – call for human beings that have been standardized in a modular sense, this having been the essential prerequisite for efficiency improvement and administration since the 19th century. Grid-based systems that serve as a means of gathering all kinds of data are, to begin with, neutral tools that treat all gathered data equally. In extreme cases of abuse, such as those witnessed during the dictatorship of the Third Reich, these systems can become cruel instruments serving the separation of the “normal” from the “abnormal”. Within the context of a totalitarian state, the grid system becomes a “leveller” in the sense that all forms of otherness are forbidden.

Like hardly any other structure, the grid is a paradox in itself: democratic or totalitarian, a centrifugal or a centripetal force, materialistic or spiritual, rational or irrational. 4 Thus it could be used by artists of the 20th century for an unimaginable multitude of visual solutions ranging from the severe and rigid to the playful and irregular. 5 KlausStaudt always understood the grid as a rational instrument that could be used as a means of rendering an equitable – not levelling or discriminatory – structure visible and transparent.

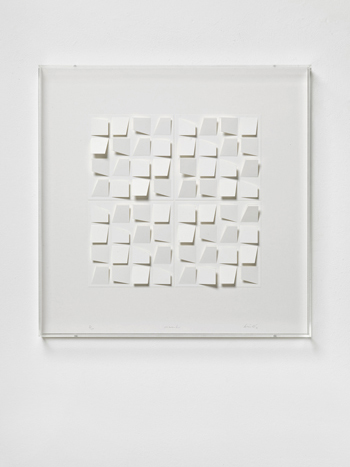

The stringency and foresightedness with which the art student Klaus Staudt set out the beginnings of his oeuvre during the early 1960s cannot fail to astonish us. Everything he developed in the course of his career, right up until the present, was already there. His time as an assistant and master student of Ernst Geitlinger from 1963 until 1965 and as an assistant of Georg Meistermann from 1965 until 1967 could be used profitably for experimentation with grid-based structures. He no longer worked with egg boxes but mainly with wood and emulsion paint. The arrangements of uniformly shaped elements became increasingly complex. Staudt began to alter their positions, turning them, inclining their surfaces, tilting them. Sometimes he would experiment with effects obtained through altogether fortuitous arrangements of the elements, sometimes he would base these arrangements on a strictly systematic approach. A series based on a fortuitous arrangement of the elements was developed as early as 1963. This comprised 34 x 34 small-sized prisms with varying angles of surface incline mounted on a support measuring 70 x 70 cm (35°– 60°, 1963, fig. 5). Only a short time later Staudt introduced a second level into this system, which not only made the elements seem to hover but also rendered the cast shadows – and hence their effect – much more complex. Staudt finally discovered Plexiglas as the ideal material for his purpose. Indeed, it was with this material that he was henceforth to work in all its possible variations, from transparent to translucent to coloured. It was with Plexiglas that he was able to create not only particular light effects but also the blurriness that has increasingly been a feature of his works since the 1970s (Tribute to Combinatorics, 1976, Fig. 6)

Staudt rang all the possible changes with these simple elements, reduced as they were in shape, line and colour, experimenting with such mathematical constellations as permutations, factorials, combinations, accumulations and a great many more. But in order to demonstrate their optical effect he was always dependent on the grid, the uniformity of which was at the very core of his experiment. Indeed, Staudt had realized very early on in his career that he needed only very few components in order to aestheticize effectively the complexity of the permutations. His experiments could so easily have tipped over into disorder, into chaos even, but the structure always remained in sight thanks to the limitation imposed by the grid, for the rules that govern Staudt’s reliefs and sculptures are never without the grid as their basic parameter. The grid has a moderating effect on the immense diversity of possibilities manifest in each and every one of Staudt’s works. While the light is always an incalculable factor that permits ever new visual effects depending on the relational position of a relief or a sculpture, the grid remains an unshakable constant. Staudt confirmed this elementary function of the grid when he wrote: “The grid serves as the basic layout for the distribution of the various elements. It forbids the unreserved use of hierarchical orders. Isomorphic and homeomorphic solids – either separated or mixed – are arranged in regular alternative repetition or according to the rules of combinatorics.” 6

It is to Klaus Staudt’s merit that he has never once allowed the grid to lapse into the irrational or into the hierarchical. For a grid can also be irregular and produce completely different optical effects. 7 But Staudt had been influenced very early on by the information aesthetics of a Max Bense and saw his grid elements rather as signs. In this context, the rules to which the artist subjects himself with each new creative process may be likened to a computer program in which the grid is an indispensable part of the system. If we continue the analogy of the computer, the grid is the hard disk, the hardware, while the various elements are the software. Thus, while the grid is indispensable and elementary in the art of Klaus Staudt, it is also so self-evident that its importance is so easily overlooked.

1 Das Bild als Denkmodell. Klaus Staudt über Klaus Staudt, published by Kunstverein Speyer, Harthausen 2007.

2 Manzoni began his series of »Achromes« in 1958. He used cotton wool, feathers, wool or dough and mounted them in grid form on the support.

3 This form of grid is largely featured in the works of such artists as François Morellet and Ludwig Wilding.

4 Cf. Rosalind Krauss, »Grids«, in: idem, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Cambridge, Mass. and London 1985, pp. 8-22. What might at first seem illogical is shown by Krauss – using the works of Piet Mondrian as examples – to be altogether plausible. The paradox is essential to the grid and hence renders it so very useful for a whole diversity of artistic intentions and appropriations.

5 Cf. exhib. cat. Rasterfahndung. Das Raster in der Kunst nach 1945, edited by Ulrike Groos and Simone Schimpf, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, Cologne 2012.

6 Cf. Das Bild als Denkmodell. Klaus Staudt über Klaus Staudt, op. cit. (note 1), p. 15.

7 Such artists as Günther Förg, Sigmar Polke and Thomas Bayrle, who likewise worked with grid-based structures, emphasized rather the irregularities of these structures.

Born in Darmstadt in 1973. Studied art history, history and Romance studies in Mainz, Dijon, Freiburg and Paris. In 2005 she received her doctor's degree for her dissertation on French art of the 19th century. From 2006 she was the curator for post-1945 art at the Kunstmuseum in Stuttgart, where she was also deputy director from 2009. Since 2013 she has been the director of the Museum für Konkrete Kunst in Ingolstadt. She has curated numerous exhibitions of contemporary art, including the great thematic exhibition »Rasterfahndung. Das Raster in der Kunst nach 1945« (Tracing the Grid. The Grid in art after 1945).

1 Gabo, Naum: Plastik: Bildnerei und Raumkonstruktion (1937). Here quoted from: Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, by Herschel Browning Chipp, Peter Selz and Joshua C. Taylor, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles and London 1968.

2 Quoted, in translation, from: Alsleben, Kurd: Ästhetische Redundanz, 1962, p. 13.

3 Quoted, in translation, from: Staudt, Klaus: Relief konkret, 1981, in: Klaus Staudt: Das Bild als Denkmodell, Harthausen 2007, p. 42.

4 Quoted, in translation, from: Hans Schwippert 1952, as quoted in: Monika Wagner, Das Material der Kunst. Eine andere Geschichte der Moderne, Munich 2013, p. 187. By contrast, the shaping properties of such materials as bronze were highly esteemed.

5 Riese, Hans Peter: Klaus Staudt Monografie, 2002, p. 19–20.

6 Arghir, Anca: Transparenz als Werkstoff, 1981, p. 8. Arghir maintains that the rejection of these traditions was first and foremost a rejection of the mimetic character of the work of art.

7 Riese, op. cit. (note 5), 2002, p. 17.

8 “The shadow, the transparency and the semi-transparency of the glass and the white are the connecting medium of the structural fields and layers of my sculptural pieces. […] White is the message of brightness and immateriality. White is open to light and changes according to its degree on radiance.” Quoted, in translation, from: Staudt, Klaus: Die Farbe Weiß, 2001, in: Klaus Staudt: Das Bild als Denkmodell, Harthausen 2007, p. 82.

9 The artist in conversation with the author on 19th March 2016.

10 Ibid.

11 In the aforementioned Darmstadt conversation of 1952, Hans Schwippert draws comparisons between the new plastic materials and the ’time-honoured’ material of wood: “Hitherto we could bend wood only so far, and then it would break. But these new materials say: ‘give me a pinch of this or a knife-tip of that, and I‘ll do anything you want.’” Quoted, in translation, from: Wagner, op. cit. (note 4), p. 190.

12 Staudt also produced embossed prints in 1979, 1982 and 1984 as part of his work for publications, but his use of this technique was discontinued after then.

13 One version of the sculpture is located at Otterndorf, while a second one was erected in Neu-Ulm in 2016.

14 The sculpture was created for the Peter Schaufler Collection (Sindelfingen), but so far has not been erected.

15 Cf. Enzweiler, Jo, and Rompza, Sigurd (eds.) Klaus Staudt. Werkverzeichnis 1960–1999, Saarbrücken 1999, p. 132.

16 Augat was a physician who was greatly interested in furthering contemporary artists, to which end he had a private gallery at his home in Otterndorf. The gallery was called studio a and, between the years of 1961 and 1966, exhibited the works of young artists. It was from the collection of the gallery that today‘s Otterndorf Museum of Non-Representational Art developed. The museum was able to open in the 1980s, thanks not least to the efforts of Klaus Staudt.

17 Quoted, in translation, from: Enzweiler, Jo, in the foreword to: Jo Enzweiler and Sigurd Rompza, (eds.): Klaus Staudt. Werkverzeichnis 1960–1984, Saarbrücken 1985, p. 7.

Born in Munich in 1983. Studied art history, Italian philology and the history of Byzantine art at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. Following several years’ involvement in museum and exhibition projects, she is currently working on her doctoral thesis on the life and work of Klaus Staudt at the University of Regensburg under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Christoph Wagner.